The short answer to the question “Does white balance matter” when the final output is black and white” is yes. As usual, the longer answer is a little more complicated. In many, possibly most, circumstances white balance has an extremely small influence on the final black-and-white output. The lighting contrast of the scene, the color sliders in the black-and-white conversion, and all of the other post-processing controls typically have far more influence.

Here’s the thing, white balance rendering happens at the beginning of RAW file conversion. Almost everything else comes after. There are some circumstances where the white balance matters. When it does, it matters a lot. The initial white balance can make or break the rest of your final black-and-white output.

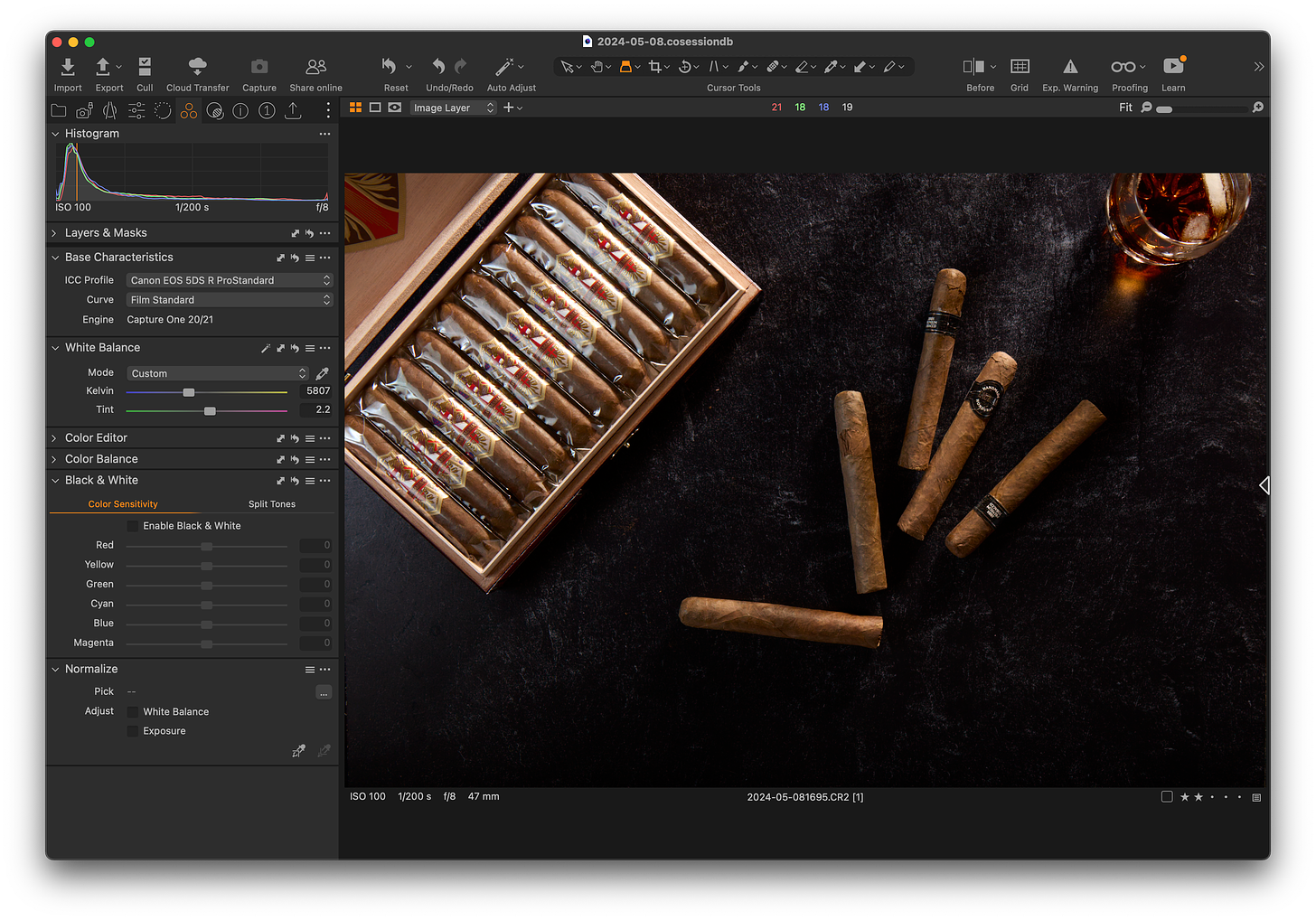

The photo at the top of the post was not intended to be rendered in black and white. The fact is from the very first test shot I intended the final output as color for both online and print consumption (a promo for some events I am hosting this summer). I wanted the feel of a summer evening when the sun is getting low in the clear blue sky. What you see at the top is “neutral” color balance. Neutral means the mix of light is neuralized to a ColorChecker WB target. I’ll probably end up rendering it a fair amount warmer.

As I was making a few images similar to above the warm, hard sunlight mixed with cool blue shadows reminded me of many landscape scenes made in the early morning or early evening and how much white balance can matter when performing a black-and-white conversion. I decided this shot could easily illustrate how much WB matters in a few common cases.

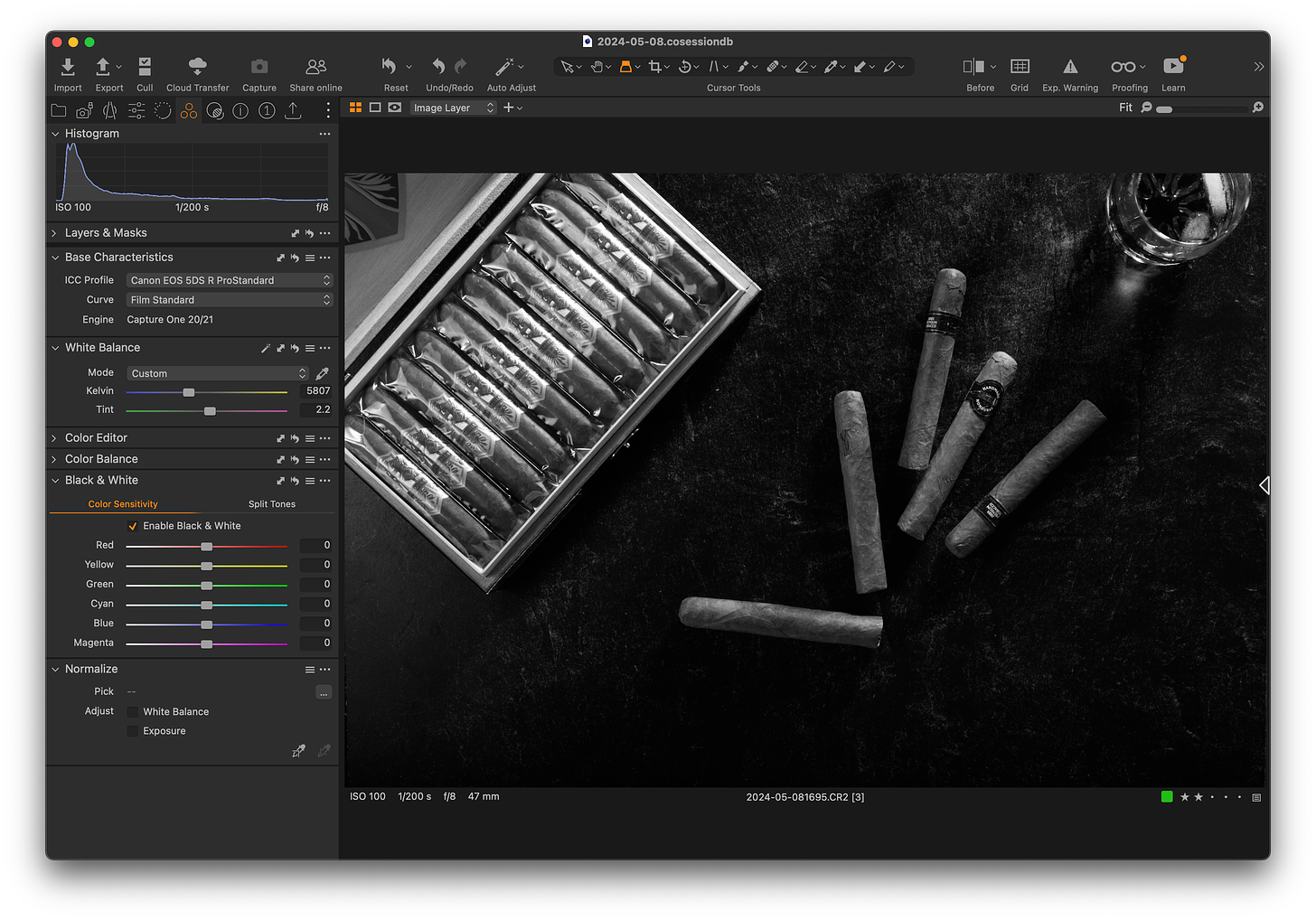

Let’s start with a strait-up black and white conversion:

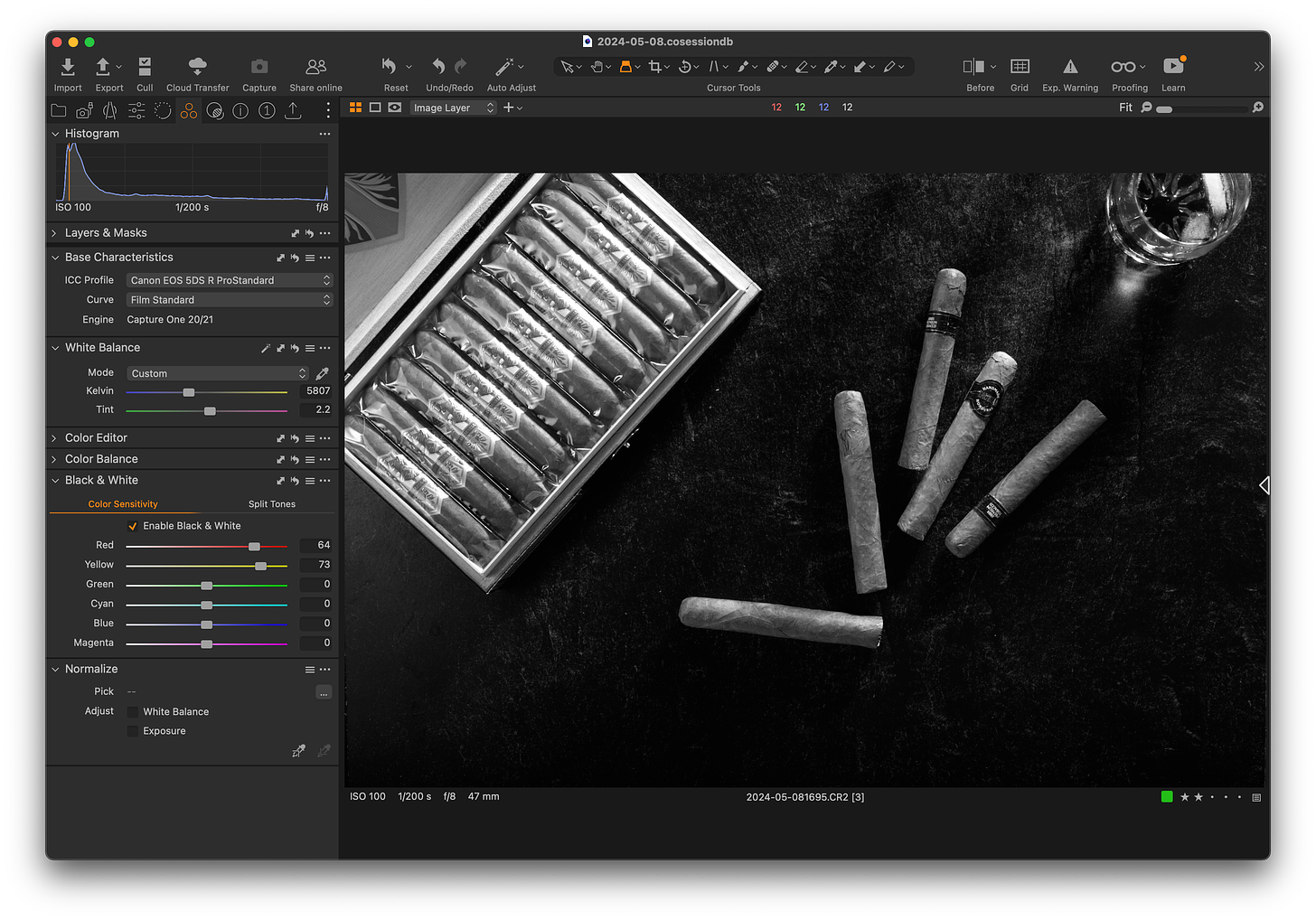

Kind of bland without those warm saturated colors. Let’s see what we can do with just the black-and-white mix controls. This should be easy we’ll brighten the reds, oranges, and yellows…

A significant increase in subject separation with no other adjustments and a great starting place for tweaking overall exposure, contrast, etc. Now let’s see what happens when the white balance is shifted substantially far earlier in the RAW conversion.

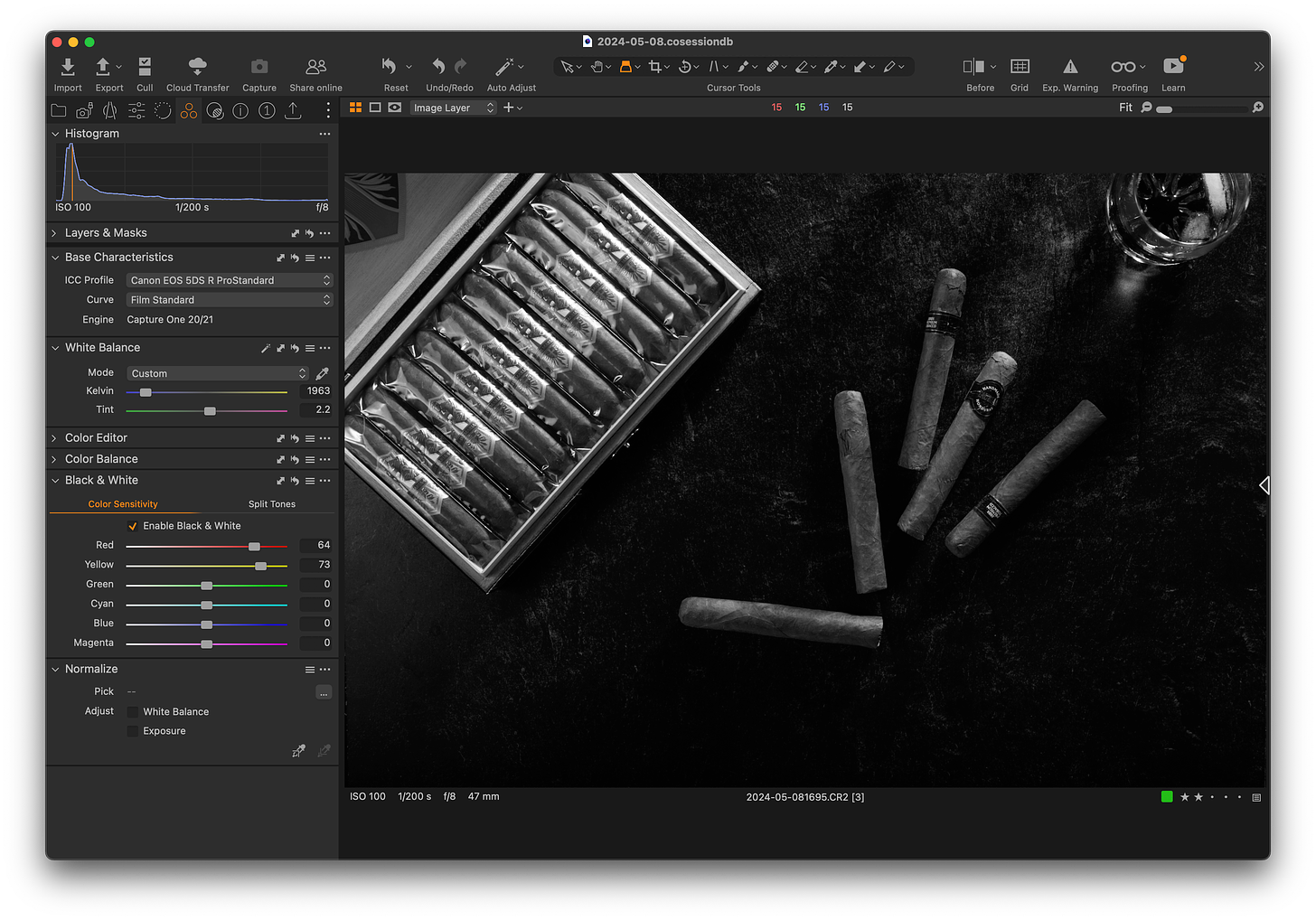

I’ve artificially cooled the WB down. Take a look at what is going on here with the same conversion. It’s far duller than even the straight-up neutral white balance. Without adding a bunch of additional screenshots, trust me it’s impossible to separate the subjects with any of the black-and-white conversion sliders related to color. Although contrived and extreme it illustrates a broad range of conditions that compromise a great black-and-white shot when there are significant color casts due to WB when shot or not corrected before conversion.

While overall lighting contrast is utmost there are hundreds of photographs where I’ve tweaked the white balance a bit to allow a fine degree of contrast control in the final black and white output that were make or break for the final print. This kind of thing is important in landscape photographs far more than you’d guess, especially during early and late hours (when great landscapes are made).

Thinking about it creatively can also help you achieve the perfect black-and-white conversion. Turn it upside down, and introduce a WB color cast that blends colors to isolate a particular more important part of the scene.

When else is it important?

If you’re trying to match the results of black and white film white balance can be extremely important. Start your BW conversion with a daylight white balance. This is true no matter if a color filter was used or not. Doing this will allow you to precisely match the digital using the typical color mix controls in the black-and-white conversion.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading your insights on the importance of white balance in black-and-white photography. It’s fascinating how the initial white balance setting can significantly impact the final output, especially in landscape photography. Your detailed examples, like the adjustments made to the red and yellow sliders, clearly illustrate the creative possibilities and technical considerations involved. Thanks for sharing such valuable tips and techniques!

Ok, but… please correct any misconceptions in the following.

My functional understanding of white balance is that all possible settings other than Auto are static. Daylight will yield the same temperature and tint regardless of the photo for all shots, both in camera and (with separate presets) in Lightroom etc. So if you’re doing any post with RAW files WB in camera really doesn’t matter; one can always reset WB presets after the fact to what the camera settings would be, or anything else.

Auto WB in camera and in Lightroom and with the dropper all attempt to set WB based on a perceived neutral gray setting within the shot; the difference being whether the camera or software or user picks the area to determine that neutral tone. The reason one would always use Auto WB in camera is simply to see what the camera thinks is neutral and have that input while adjusting in post - more reference data to work with.

Using the WB dropper on a given area will give the same temperature and tint regardless of the profile; color, monochrome, or whatever. Playing around with the WB sliders - or WB dropper in different areas of a monochrome image - does change the resulting grayscale values in interesting and non-linear ways. (See how the histogram changes as you adjust Temp/Tint!) Definitely worth exploring.