If you’re reading this hoping for the forty-thousandth tutorial on manipulating images in Photoshop or the newest magic push-button solution for making your images epic, stop reading now.

I am using an older sense of the word ”editor”. Choosing what images to use, how and where to use them, and how many will do the job. The edit can be excruciatingly difficult, especially with your own images. I find the task more vexing in the digital age. It’s too easy to pile up mountains of unused, unseen, and un-curated photographs. I’m guilty. This is the case for every photographer I’ve ever known when it comes to personal work. Jobs, as in commercial jobs, are much easier. Jobs have goals, deadlines, and direction.

Here’s an open secret; Not all constraints are bad. The right constraints can make you more creative, more productive, and improve your enjoyment of the photographic process. I’m sure you’ve heard dozens of variations on this. Use one lens and one camera, use one light, photograph one subject for a month, make one good picture every day for a year, make one good portrait every day for a year. These are all constraints, many of them are helpful if you’re lost in the weeds. I want to focus on the other end of those pictures made. What happens after you make them?

I’ll suggest that you stop treating your pile of images as your own personal stock agency. I’ve noticed everyone does this now. Everyone meaning photographers, non-photographers, and every cell phone wielding individual on the planet.

A big pile of pictures stored away in an invisible archive to be retrieved when a situation prompts digging a particular picture up. Typically the end result is a two second display on a cell phone. The photo-sharing sites and services are no better. Instagram is an ever-scrolling mess of random pictures you can search through. This is what stock agencies do. A giant pile of pictures to search through with the editorial voice and selection left to you.

Physical portfolios, albums, and books are magnificent constraints. I was reminded of this over the last two months as I set out to survey a 2021 “lay of the land” for book printing services. The first decision was defining what to produce.

Here’s what I came up with:

A softcover book

8.5in x 11in page size

Somewhere between 50 and 100 pages

Color photographs

Produce output on paper in August

Why these parameters? I wanted parameters common across many print service providers. Letter-sized pages are common, 50-100 pages would satisfy minimum page counts handily, and I wanted to compare color accuracy and consistency. Softcover vs Hardcover? I wanted to keep it cheap, some services don’t offer hardcover. I wasn’t looking for expensive binding options at this point in my research.

The last one and the most important; I wanted to compare the mass-market providers by the end of August. Without a time constraint, projects tend to go on forever with no tangible results. Decisions are deferred, countless revisions are made, one project morphs into something completely different, or a new shiny object comes along to distract you.

Those constraints weren’t completely arbitrary but could be if you chose. It doesn’t matter what factors drive the box you build around producing something. Make them up if there’s nothing that occurs naturally. The important part is I now had a size and shape. I also had another constraint, the images had to be color. I had only one suitable pile of images made recently.

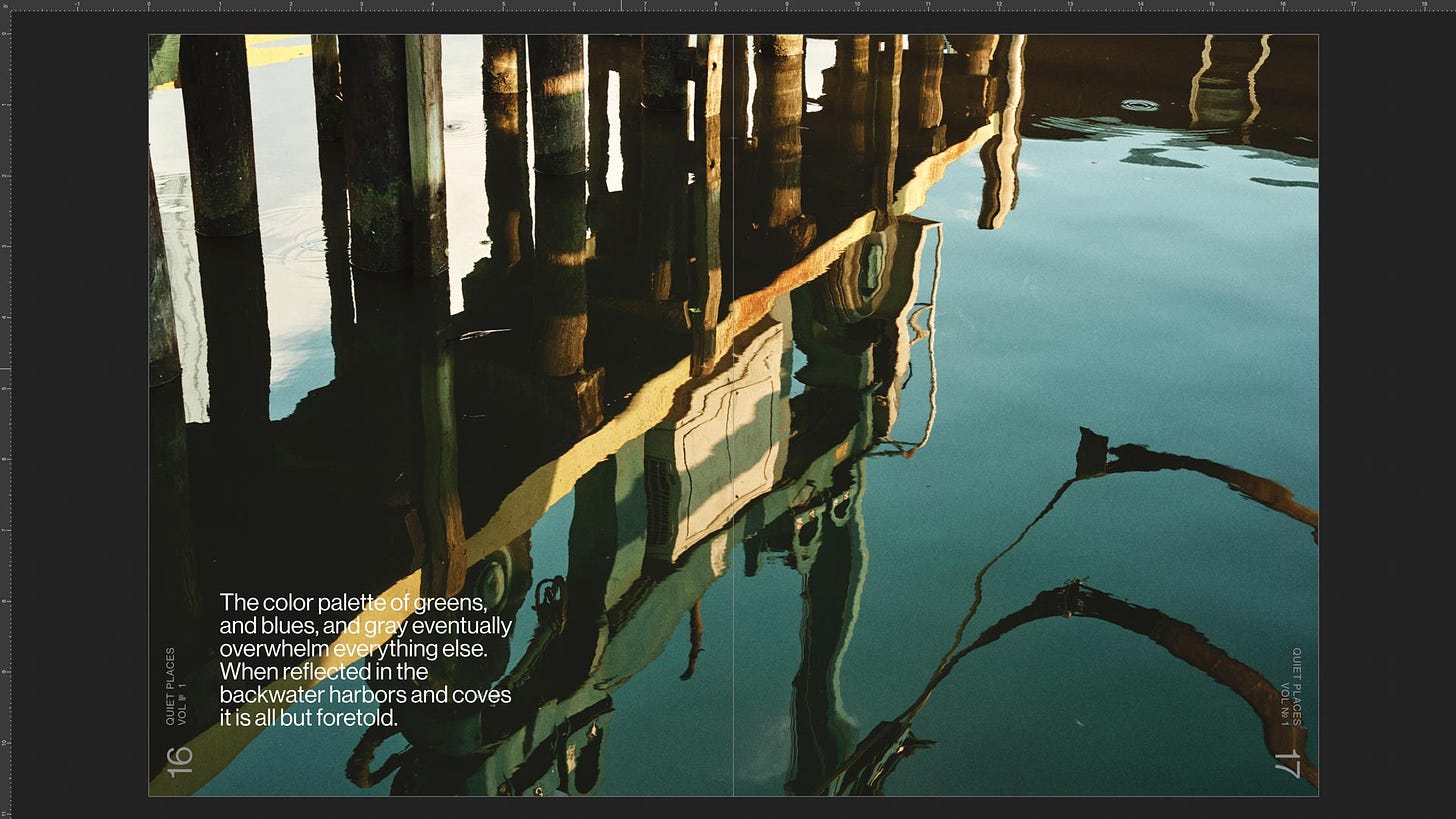

As part of my post-COVID anti-funk efforts, I forced myself to take evening walks. I had to. I needed to get off my rear-end and out of the house. I needed a habit. Luckily, I made part of that habit to take a camera with me.

Once a week I’d look at the photos I made. I’d rate a few as “not so terrible” and move on. That’s probably what you do with photos you make. Take a look, mark a few that speak to you, maybe post a few on social media, and continue down the road of making more.

Aside: I’m a terrible landscape photographer. My local area is notoriously difficult to make pictures that make any sense at all. Those two things combine to produce a bonanza of terrible pictures waiting to happen.

With the daily walk images selected as the pile and a vague local theme established, I started to layout a book design. Nothing complicated but informed by the fact that it would not be text-heavy. The picture layouts I toyed with were driven by the proportion of horizontal images versus verticals that were in my rough selects.

I leaped in, placing the not so terrible pictures into the layouts. As I did this the seeds for an editorial voice emerged. That voice in turn helped me make judgment calls on sequence and juxtaposition. The constraints I defined at the start took on a clear shape, some pictures wanted to be big. Other pictures wanted to be small. I might have a story and rhythm now…

My self-imposed deadline was approaching. Time to stop foolin’ around with re-re-re-arranging things, I liked the layouts I did a week ago better. I did the captions, wrote a brief introduction, and a nobody-cares epilogue with techno-crap and other detritus. You know, things that cause anxiety where you feel compelled answer questions nobody will ever ask.

Done! Except for the cover. Pages uploaded to the first provider, everything ready to go. I procrastinated slapping together a cover for two days. I finally got sick of thinking about it and slapped the world's worst cover together in the format demanded.

A few days later the hard copy proof was on my front doorstep. I briefly hesitated to open the box the way I might if I was submitting work to someone else’s publication. Nobody wants a rejection letter. The other less evolved side of my brain couldn’t wait to see and touch the object inside. That side won. I opened the box immediately.

I hated the cover but not as much as I did when I made it. The cover was fine, who cares. Now for the content… I loved it. A couple of normies1 I showed it to loved it more. I didn’t shove it on them, they saw the cover and asked to see it. Does anyone ask you to see the pictures on your phone? Ahhhh, the power of print.

Can you see the difference a few constraints can make? The big constraint is the production of a physical object.

Producing finished work is how you become a better photo editor. Reading this essay or “knowing” this doesn’t make you a better photo editor, a better photographer, or more productive. Yet another post-processing treatment on the same image you’ve already done a dozen times is not productive. Producing a finished piece of work and putting it out there is productive. It’s easy to forget this. More accurately, delaying a finished body of work indefinitely is common for personal work.

Let me know if you’d like walk-throughs of the layout process, detail about the editorial decisions I went through, and all the ugly fat of it included. Share your successes or failures from an editorial perspective, or publicly put a stake in the ground in front of all of us if that helps you get something done.

Non-photographer people that care much more about what the picture is than how it is made or how sharp it is or if it violates the dictator of thirds. ↩︎

I'd be interested in how you make your editorial decisions. I can eliminate the real chaff and select the very few really good ones but can never really judve the bulk of the just good work.

I appreciate the candor and tone with which you write your newsletters. It’s refreshing to read how-to with “nuts and bolts” (and warts and all). Thanks!